Why Can’t We Just Add 5lbs To A Lift Indefinitely?

Lifting is fun and addictive, perhaps the best addiction there is. Very few things in life provide as clear evidence of progress as lifting weights. Last week you deadlifted 205 pounds for a set of 10 reps, and this week you’re deadlifting 215 pounds for a set of 10 reps. Good job, you got stronger! Even better, next week you plan to deadlift 225 pounds for a set of 10 reps. Wow! At this rate, you’ll have a world record in no time! Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. Life would be so much simpler if it did. So why do we hit plateaus and stop making perceivable progress? This post will give a cursory overview of how to keep progressing, even if it isn’t by 5 or 10 pounds a week, why plateaus occur, and what you can do to avoid them.

The model I just described, of adding 5 or 10 pounds to a lift each week, is a simplified version of what is called linear periodization. Linear periodization is a systematic approach to organizing a training program over a period of time, with the goal of gradually increasing either intensity or volume. When we train, we signal to our body that this is a task we should get better at. Our bodies interpret that signal by recovering and getting stronger. Now, when we train again, we need a larger stimulus to keep adaptation going, so we progressively overload the lift to keep progress going. But as anyone who has ever trained for more than a few months in a gym with any sort of structured training program will tell you, eventually, the well dries up, and you just can’t add any more weight to the bar without sacrificing form.

The way I think of it is like accelerating a car. If the car is going 0 mph, it takes a bit, but not much effort for it to go from 0 to 40 mph. It takes a bit more energy for it to go from 40 to 80 mph, even though that is technically the same difference in speed. And it takes even more effort to go from 80 to 120 mph. A similar law of nature applies to the gym. It’ll be easy to make progress at first, harder the further and faster you go.

There are usually two main reasons why this is the case within the scope of a single program. The first is recovery. It is more fatiguing to lift 105 pounds than it is to lift 100 pounds, all else being equal. Compound this process over the course of several weeks, and it should become obvious that eventually, the fatigue will become too much for an athlete to recover from. And with greater fatigue comes greater recovery times, and eventually, it might become too much fatigue for an individual to recover from within the scope of a week, or whatever your training cycle is.

A simple example to illustrate this concept is that if in week 1 you are 100% recovered, and then you work out and fatigue yourself, it is unlikely that you will be totally 100% recovered before your next workout. But if you have a week between exercise bouts, you might be, let’s say, 95% recovered, which is enough to get a good workout in and even make some progress, assuming you got more than 5% stronger from last week. This process repeats, and now by week 3 you are only 92% recovered, again still enough to make progress, but this phenomenon will compound until fitness and fatigue are equal, which means a plateau has occurred, and it is time to change things up.

The second reason that a training program becomes less effective over time is that staleness sets in. My favorite way to think about this is like caffeine (I used to say beer, but either one works). If you don’t drink caffeine, and then you have half a cup of coffee, you’ll feel the effects of the drug. But if you only ever drink half a cup, pretty soon that half cup won’t really do anything, so you’ll have to drink a full cup of coffee to feel that same effect. But eventually that too won’t be enough, so you’ll have to add a shot of espresso just so that you can feel alive again. This can initiate a vicious cycle until eventually it is unsustainable and you need to take a break and resensitize. Training is much the same, where the more you do something, the more you’ll acclimate to it, until you become fully acclimated, and something will need to change.

That’s a basic understanding of why you just can’t run the same program indefinitely and expect to keep making progress. So what can we do as educated athletes to keep reaching higher and higher numbers? Well first, you should not run a program longer than is beneficial, but you also don’t want to run a program such that you aren't able to make any meaningful progress. At Verro, we almost always use 6-week cycles: long enough for a pattern to emerge, but not long enough for staleness to set in. Ideally, we should have our programs communicate with each other, capitalizing on the stimuli that are most effective, and eliminating the ones that aren’t doing much for us.

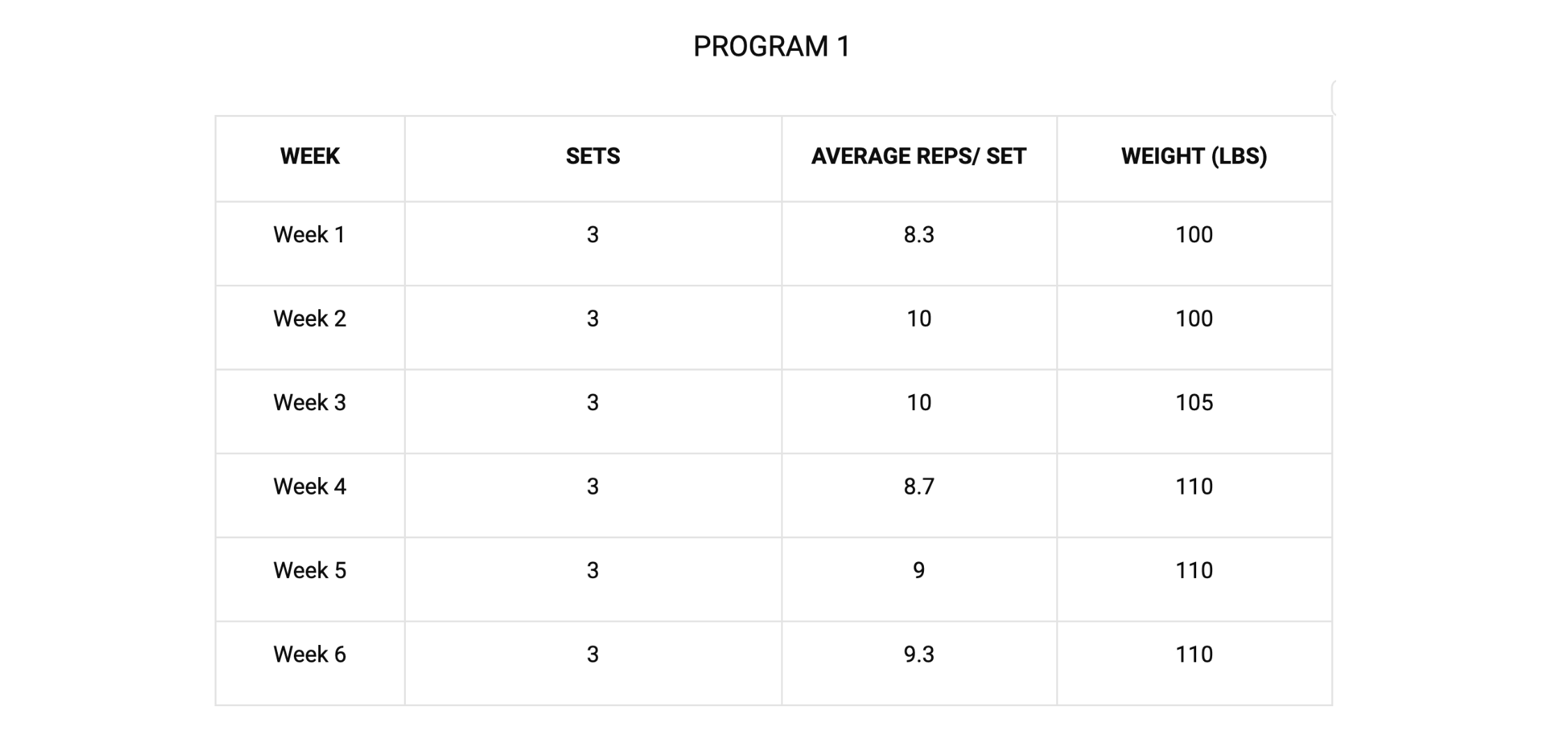

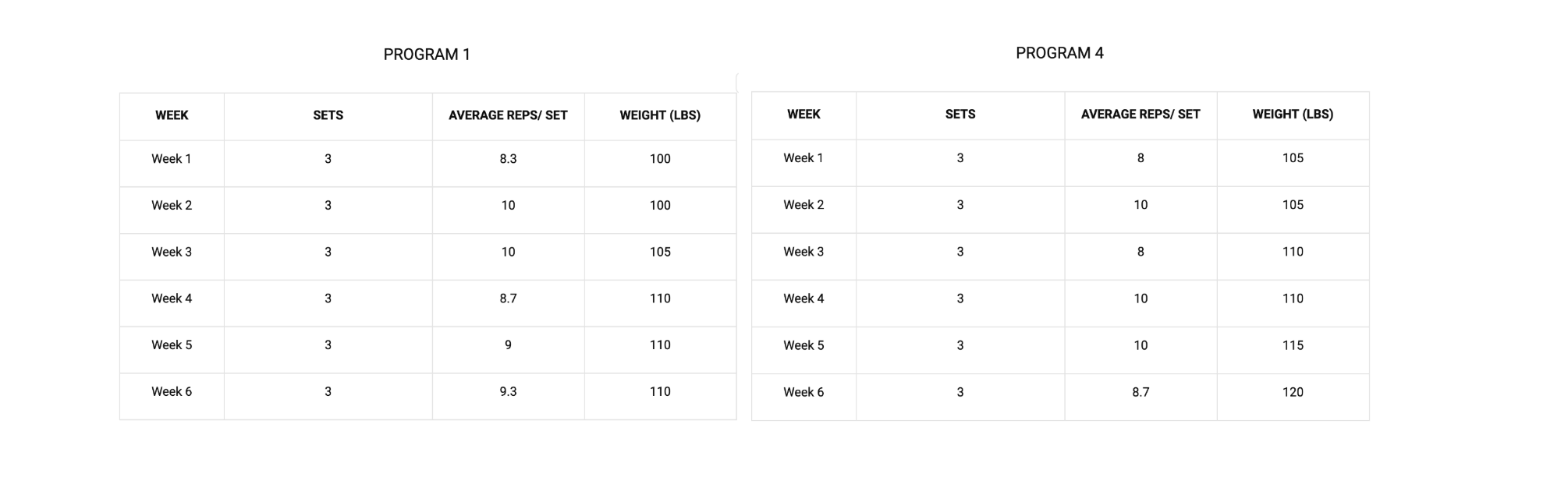

Let’s use a simplified example to illustrate the point. Imagine we have an athlete on a 6-week block, squatting for 3 sets of 8-10 reps during that program, finishing each set with 1-2 reps in reserve. Their progress might look something like this:

In the example, you can see that the athlete made good progress in weeks 1-3 but only managed an additional rep over 3 sets in weeks 4-6. We could keep the stimulus the same for an imaginary week 7, but it might also be good to try a slightly different strategy to keep gains moving forward. In such a scenario, we can deviate in several different directions. We could try a different type of squat (like a front squat or SSB), a variation of the same exercise (like pause squats, pin squats, or banded squats), or we could simply change the rep range. How you deviate, and how much you deviate, will depend on the athlete’s goals and the effectiveness of previous training. Generally speaking, you want to deviate more from things that are less effective and less from things that are more effective.

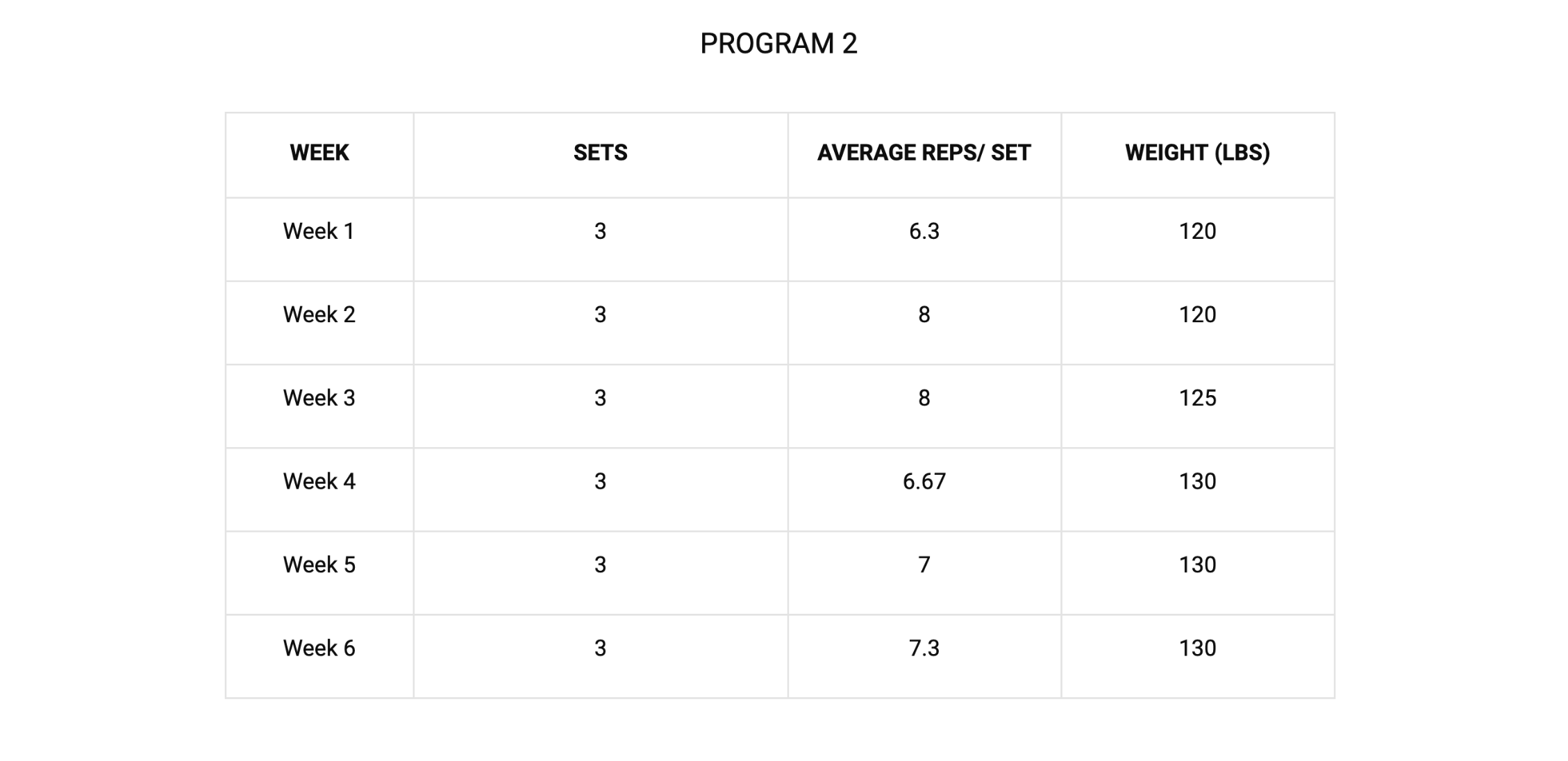

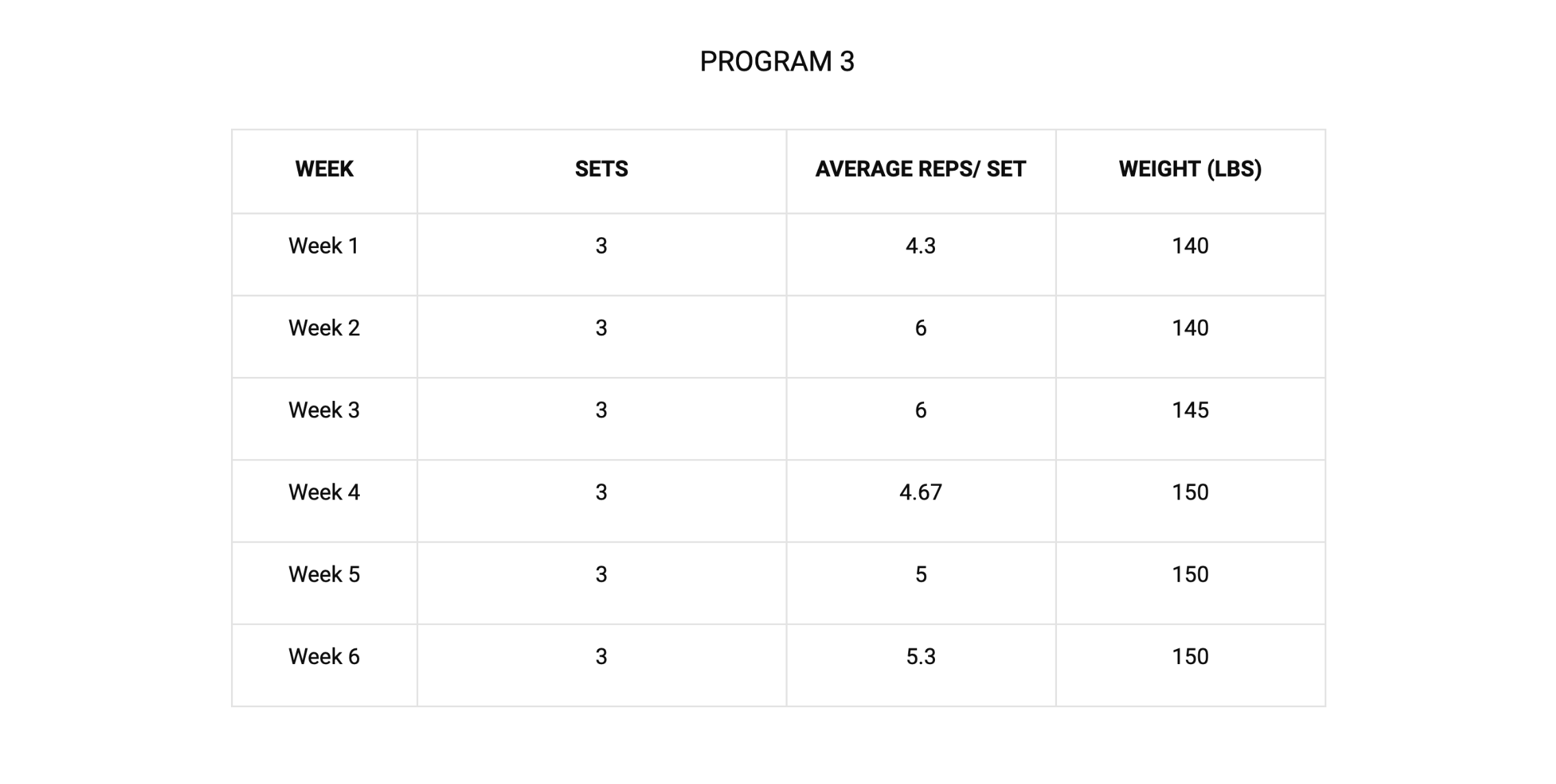

For this example, let’s imagine running two more 6-week programs where we just keep dialing down the rep range but keep everything else the same. The second program will be 6-8 reps, and the third program will be 4-6 reps.

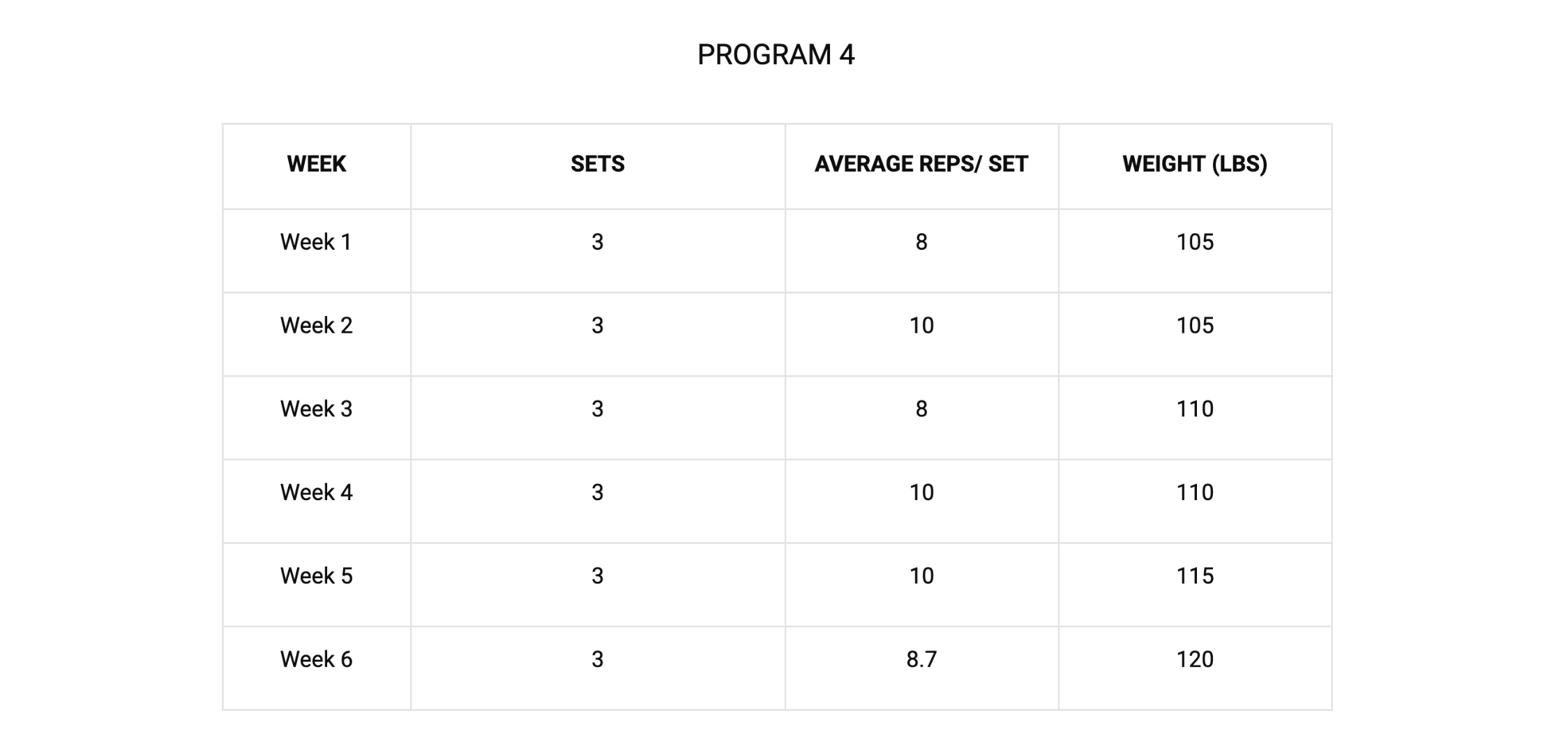

Fantastic, look at all the progress we’ve made across three different rep ranges. But now what do we do? Again, it will depend on the athlete, but let’s imagine running that same protocol from program 1 again. Enough time should have passed since we ran it to be resensitized to that stimulus, and we have been working on similar training, which should transfer well to doing sets of 8-10. A fourth program could look something like this for that same athlete:

Although some decay has occurred from where we left off on week 6 of program 1, if we compare week 1’s to each other, it’s clear that there has been significant progress between those two periods. This means we should be able to build to a higher peak, which is the case in this example.

Rarely in life is progress linear, and fitness is no exception. Plateaus are inevitable, and if I could add weight indefinitely to the bar each week until I had all the world records, I absolutely would. But by understanding the principles of periodization and the nuances of adaptation, we can navigate these challenges effectively. Through systematic adjustments to training variables such as intensity, volume, and exercise selection, athletes can continue to make meaningful progress over time. By embracing variety and periodic changes in programming, we can sustainably push past plateaus and reach new heights of strength and performance. It is perhaps more beneficial to not think about adding 5 pounds to the bar indefinitely, but rather about continuously evolving and optimizing our approach to training for long-term success in the pursuit of strength and fitness.

DISCLAIMER

The information in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider or medical professional before beginning any new exercise, rehabilitation, or health program, especially if you have existing injuries or medical conditions. The assessments and training strategies discussed are general in nature and may not be appropriate for every individual. At Verro, we strive to provide personalized guidance based on each client’s unique needs and circumstances.