The Deadlift Dilemma: Which Deadlift Is Best For Your Training?

Key Points

Deadlifts are essential in exercise programs due to their unique effectiveness in building strength, muscle, and overall athleticism. Deadlifts can be utilized in various ways to achieve different training goals, and the choice of deadlift variation depends on the individual, training status, and objectives.

There are three main types of deadlifts: conventional, sumo, and hex bar. Each variation has a different emphasis, but all can be used to achieve different training goals.

Scientific studies reveal that muscle activation varies among deadlift variations. Factors such as stance width, torso position, and grip influence muscle engagement, with each variation emphasizing something different to varying degrees.

While scientific insights are valuable, the practical application of deadlift variations should consider individual goals, preferences, and adaptability. The selection of deadlift variation should prioritize progress and adaptability within a structured training program.

Introduction:

Deadlifts are one of the most popular and effective exercises utilized by athletes. Every serious exercise program should include some variation of a deadlift given the numerous benefits. Deadlifts train several muscles simultaneously which transfer over to enhanced everyday life and athleticism in a time-efficient manner. Perhaps no other exercise is as effective in building strength and muscle as deadlifts. Beyond that, they can boost metabolism, increase bone density, and aid in longevity. That said, there are many ways that one can use a deadlift in a program. Deadlifts are useful for strength by doing 1-5 reps at very high intensity. The focus is on hypertrophy (muscle growth) by lowering the weight and doing 6-12 reps relatively close to failure. Deadlifts can also be used to improve work capacity, aerobic conditioning, and endurance by including them in a circuit or going for very high reps at low weight. The best use will depend on your training status and goal. Generally speaking, there are three main types of deadlift: conventional, sumo, and hex bar, all of which can be trained in a variety of ways. Deciding on which one to do for your program can be daunting, so the scope of this article will explain what the science has to say about the differences in deadlift types. I will then give practical coaching recommendations on how to pick among the main types of deadlifts.

Let’s start by explaining the three main types of deadlift. First, conventional deadlifts (sometimes called traditional deadlifts). These are probably the most common type of deadlift. In this variation the lifter’s feet are about hip-width apart with hands just outside of the legs. Sumo deadlifts differ in that the lifter assumes a significantly wider stance, angling their toes outward, and gripping the bar inside of their feet. Finally, a hex deadlift, sometimes called a trap bar deadlift, uses a specialty bar that is in the shape of a hexagon or trapezoid. The hex deadlift uses neutral grip handles at the side. Some lifters prefer to use the hex bar since they find it more comfortable to hold and lift. As a coach, I usually start a beginner client on the hex bar to teach the hinge pattern, as it seems to be more intuitive and less intimidating. Now that we have a better idea of the three main types of deadlifts, let’s investigate what the scientific literature has to say about their differences.

MUSCLE ACTIVATION DIFFERENCES

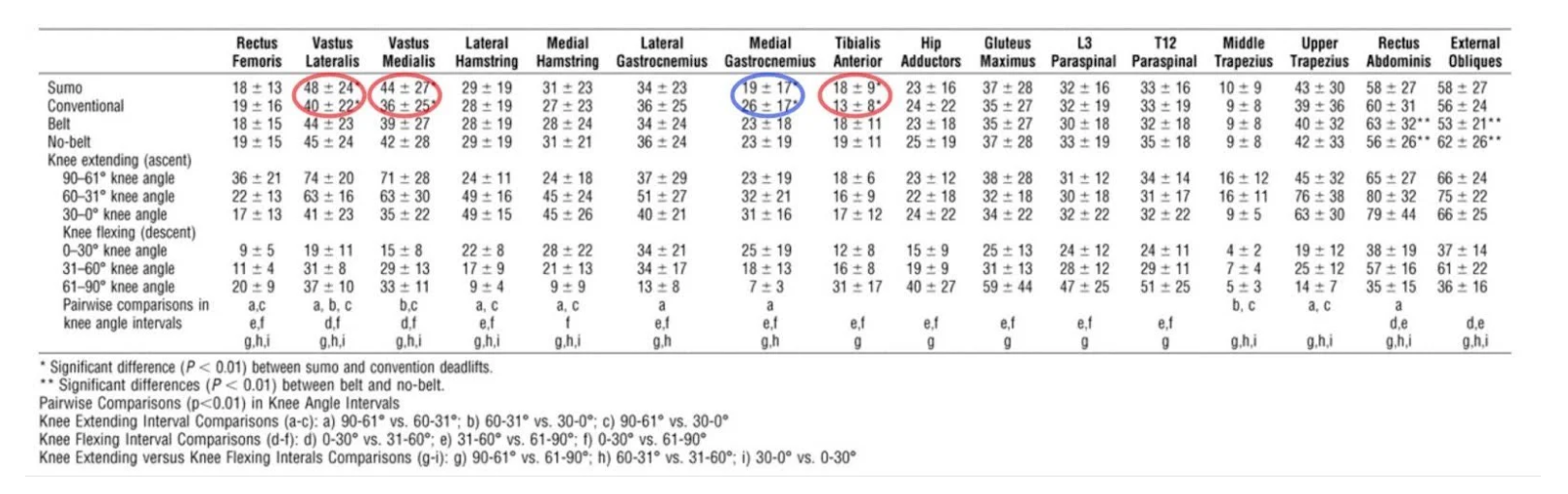

Even though all three variations have the goal of accomplishing the same thing—picking something heavy off the ground— changes in body position will elicit a different response in muscle activation. This claim is supported by exercise science research. If we compare conventional to sumo deadlifts, a 2002 study by Escamilla et al, sumo deadlifts had significantly higher quad activation, specifically in the vastus medialis and vastus lateralis (two main muscles of the quads), compared to conventional deadlifts. There was also more activation in the tibialis anterior (shin muscle), for sumo deadlifts. However, conventional deadlifts had greater activation in the medial gastrocnemius (part of the calf muscle) (1).

Table 1

Electromyographic comparisons (mean ± SD) between sumo and conventional deadlifts (collapsed across all knee extending and knee flexing intervals and both belt conditions), between belt and no-belt (collapsed across all knee extending and knee flexing intervals and both deadlift styles), and between knee angle intervals (collapsed across both belt conditions and both deadlift styles); data were normalized and expressed as a percent of a maximum voluntary isometric contraction.

Source: Escamilla et al. (2002).

The reasons for this are biomechanical. Since the stance is wider performing a sumo deadlift it results in greater abduction of the hips and knees. A wider stance and greater abduction angle likely contribute to increased activation of the quadriceps as well, as these muscles are more engaged in knee extension. Sumo deadlifts also typically involve a more upright torso position compared to conventional deadlifts. This upright posture may place greater emphasis on the quadriceps to extend the knees and maintain stability during the lift. Furthermore, the wider stance of the sumo deadlifts may also require more dorsiflexion of the ankle to maintain proper alignment of the lower body. The tibialis anterior, which is responsible for dorsiflexion of the foot, would thus be more activated in sumo deadlifts compared to conventional deadlifts. The medial gastrocnemius is likely more activated in the conventional deadlift since the narrower stance and more forward-leaning torso position places greater demand on the gastrocnemius, especially in maintaining balance and stability during the lift.

Conventional deadlifts place more emphasis on the lower back. This is because of the forward-flexed trunk position, which increases torque around the lumbar area. This is obvious for anyone who has seen a sumo and conventional deadlift from the side. So there appears to be a tradeoff between glute and low back when switching between sumo and conventional. This is backed up by the literature. A 2001 paper from Piper et al. found that the sumo-style deadlift required greater recruitment of hip muscles to move the load, which was directly correlated to the more erect back alignment (2). These findings were backed up in 2020 by a study from Salehi et al., which found that in a comparison between sumo and conventional deadlifts, muscle activation patterns during one-repetition maximums were significantly different between the two lifts. Specifically, the vastus medialis saw greater activation in the sumo deadlifts, while the erector muscles were more activated in the conventional variation (3).

Table 2

Comparison of mean and ratio of muscle electromyographic activity in sumo and traditional deadlift movements between the dominant and non-dominant legs

Source: Salehi, K. et al. (2020).

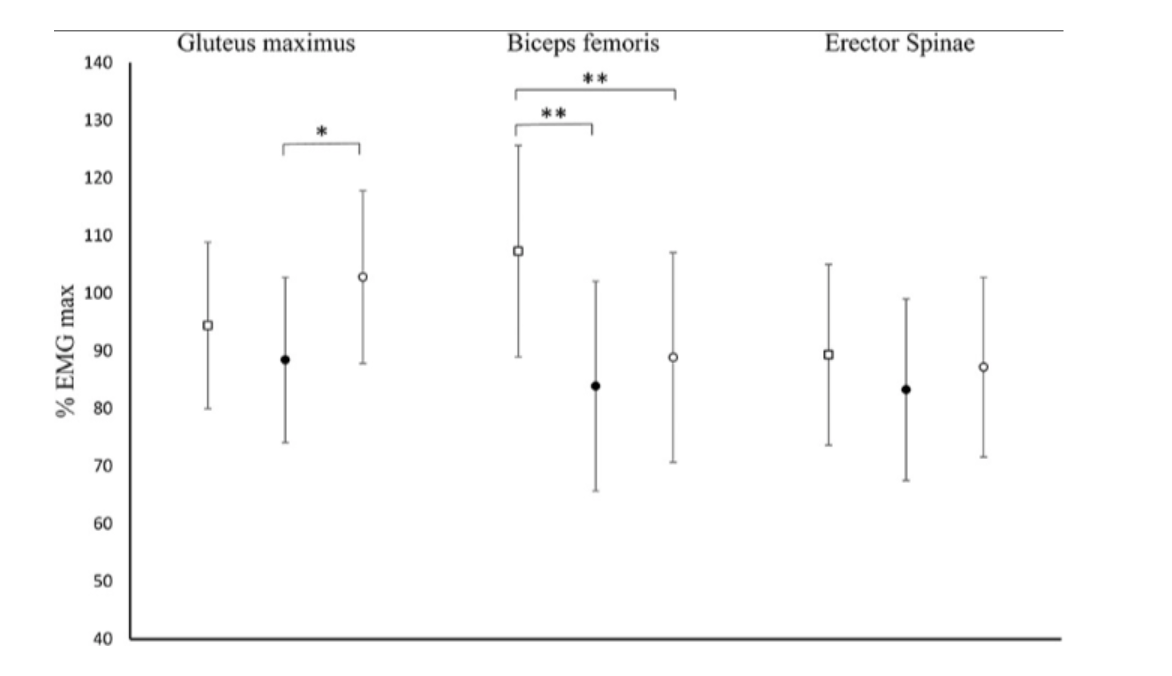

The positioning of a hex bar deadlift is unique. As such, muscle activation should be different from sumo and conventional deadlifts. This seems to be the case. A 2018 study from Andersen et al. found that the conventional deadlift was superior in activating the biceps femoris (the largest part of the hamstring) than the hex deadlift in direct comparison (4). According to the study, conventional deadlift had 28% more activation of the biceps femoris compared to the hex deadlift.

Figure 1.

Mean electromyographic (EMG) activity (normalized to maximal voluntary isometric contraction) in the gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and erector spinae during the barbell deadlift (□), hex bar deadlift (●), and hip thrust (○). Brackets indicate difference between exercise modalities (*p ≤ 0.05, **p < 0.01). Values are mean with 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Anderson et al. (2018).

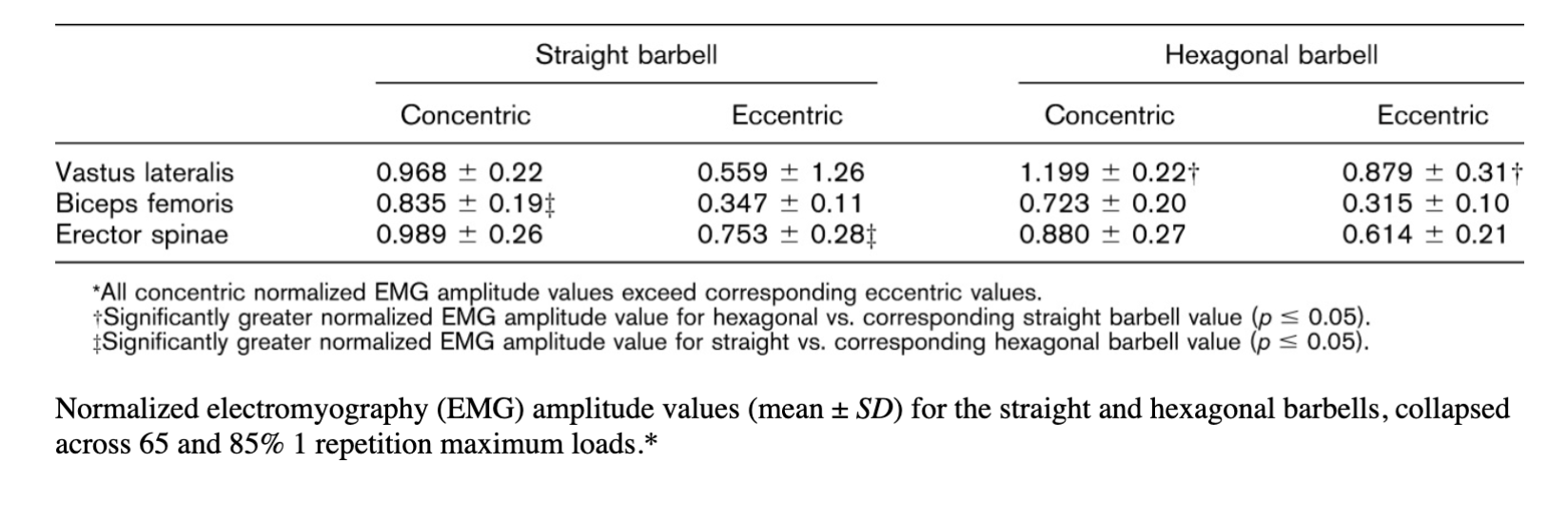

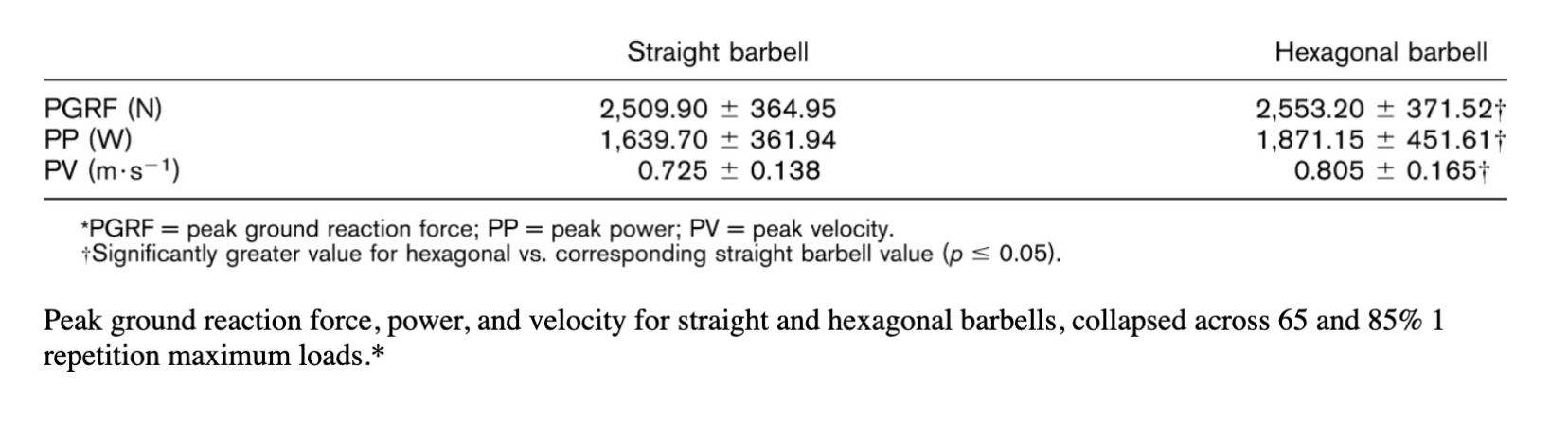

Another study from 2016 from Camara et al. found that muscle activation patterns were different between the hex bar and conventional deadlifts. The hex bar deadlift had greater activation in the vastus lateralis and had higher peak force, power, and velocity compared to a conventional deadlift (5). This suggests that hex deadlifts may be more effective for endurance or power-based athletes, or for athletes who need to develop their quads a bit more.

Table 1

Normalized electromyography (EMG) amplitude values (mean ± SD) for the straight and hexagonal barbells, collapsed across 65 and 85% 1 repetition maximum loads.*

Source: Camara et al (2016).

Table 2

Peak ground reaction force, power, and velocity for straight and hexagonal barbells, collapsed across 65 and 85% 1 repetition maximum loads.*

Source: Camara et al (2016).

A more recent study from 2020 from Flandez et al. reported that since hex deadlifts allow for a more upright posture, but with a relatively narrow stance, knee extensors activation was higher than conventional deadlifts due to a relatively vertical back and aligning with the load (6).

Studies comparing hex deadlifts to sumo directly could not be found in the scientific literature search, but some inferences from the available literature can be made. Regarding muscle activation, there appears to be more similarity between the hex bar and sumo deadlifts compared to the conventional deadlift. However, the literature suggests that hex bar deadlifts might activate the vastus lateralis and knee extensors to a greater amount compared to sumo deadlifts. This likely has to do with the fact that the knee is extended further in the hex bar, and is more similar to a squat. This may also explain why hex bars are better for force production and power. An easy way to understand this is that if one were to jump in the air, one would not want a super wide stance. The starting position would look more similar to the setup for a hex deadlift. The hex bar deadlift seems to have a distinct muscle activation pattern that can be more useful than other forms of deadlifts depending on the training goal. The body of the literature suggests that hex bar deadlifts generally provide higher activation of the biceps femoris and knee extensors, with high levels of gluteus maximus activation.

While we just spent some time explaining the differences among the main types of deadlifts, it is important to remember that they are all just part of the same family of exercise. All deadlifts train the same muscles, they just emphasize certain parts of the body more than others. However, some muscle groups appear to treat all deadlifts very similarly. For example, the Escamilla study found that when using lifting belts during different types of deadlifts, there was an increase in rectus abdominis activity and decreased external oblique activity, regardless of deadlift variation (1). I’d also expect forearm and grip activation to be similar across all forms of deadlifts, but I could not find any evidence to support that opinion.

I should also note that individual anthropometry will arguably play a bigger role in which muscles are activated in a lift. A sumo deadlifter with short arms will have to hinge over and engage more lower erectors, creating a similar activation level to that of a conventional lifter. A conventional lifter with short legs will be more upright and thus have similar activation levels to that of a hex bar deadlifter. And this is what the Flandez study found. Deadlifts had different muscle activations depending on the level of hip flexion and/or knee flexion a liter was in. There were also different levels of activation depending on the distance between the load and the center of mass, knee flexion planes, and total intensity (6). Therefore, a variety of factors can play a role in what muscles are activated when performing a deadlift. For example, the starting position of a deadlift is a bit arbitrary. The bar is almost always 8.75 inches or 22.23 cm from the ground, which is just a function of how big the diameter of the weight plates is. But this means that someone who is 6’6 is going to have to reach down close to their ankles to pick up the weight. And when you compare that to someone who is 4 '2'’, the bar would rest around their upper shin when they are pulling it from the ground. Since the relative starting positions are different for those two individuals, it will assuredly affect muscle activation for the lift, regardless of variation. This claim is backed up by a 2023 study from Moreira which found that different deadlift positions require different muscle activation (7).

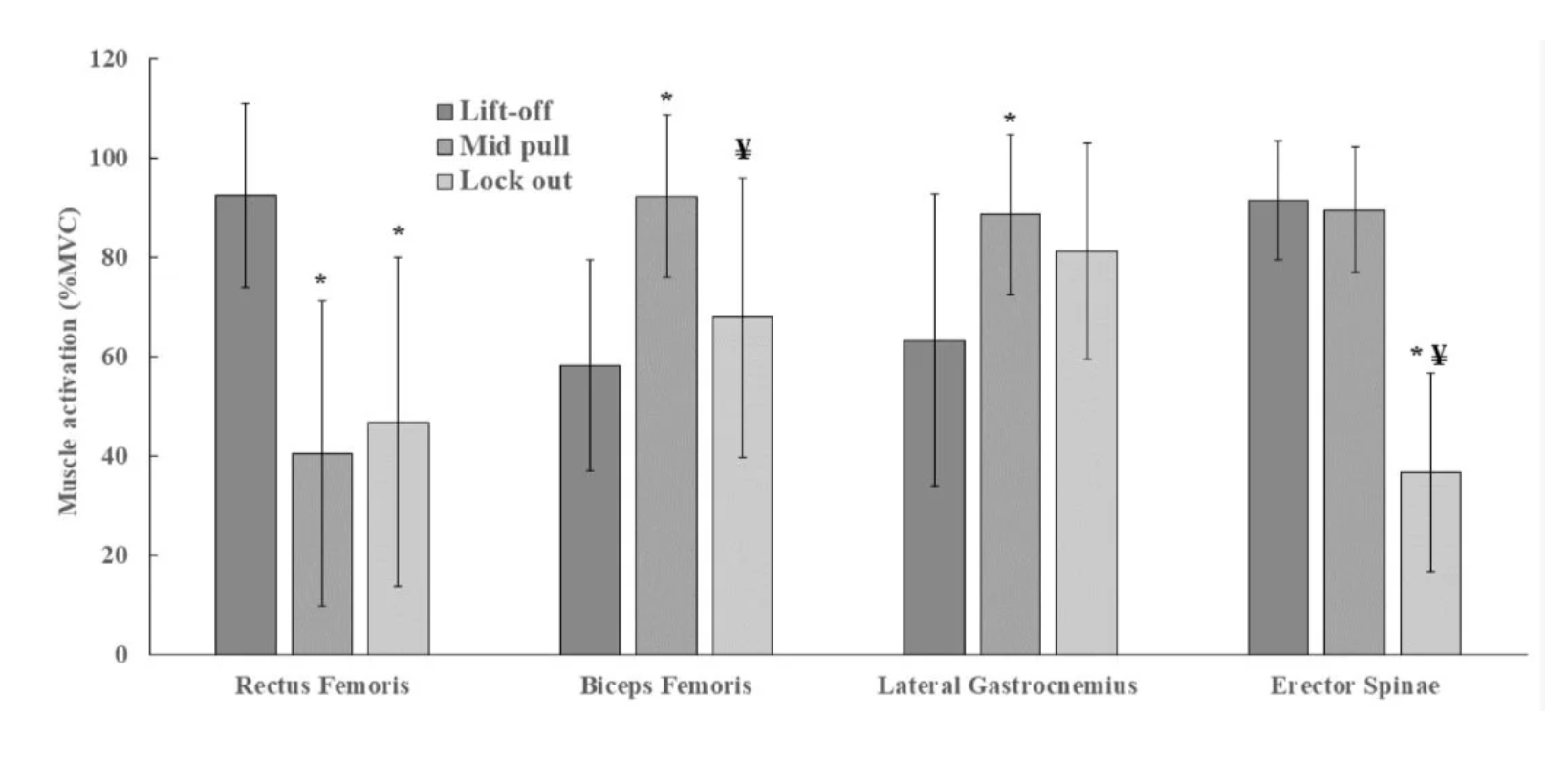

FIGURE 2

Muscle activity in relation to DL positions. * Significant difference (p<0.05) for the lift-off position. ¥ Significant difference (p<0.05) for the mid-pull position.

Source: Moreira, V.M.; Lima, L.C.R.d.; Mortatti, A.L.; Souza, T.M.F.d.; Lima, F.V.; Oliveira, S.F.M.; Cabido, C.E.T.; Aidar, F.J.; Costa, M.d.C.; Pires, T.; et al. Analysis of Muscle Strength and Electromyographic Activity during Different Deadlift Positions. Muscles 2023, 2, 218-227. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles2020016

So, we can emphasize certain parts of the musculature by changing the starting position of the deadlift. For example, performing deficit deadlifts would emphasize the rectus femoris and erector spinae more. While performing block pulls and only doing the top part of the lift would emphasize the biceps femoris and lateral gastrocnemius more.

INTERPRETATION

So that’s the science as it stands as of the date of my writing this essay. But how can this information be best applied to optimize results for ourselves or our clients? Well as interesting as all this information is, for the most part, I’m not sure how applicable it is to athletes. The reason for that is that if we focus on the minutiae of science, the big picture of the reason for deadlift training may be missed.

The deadlift is one of the six fundamental movement patterns essential for exercise and fitness. So it must be trained as part of any effective program. If the scope of the program is to develop specific musculature, then perhaps selecting a specific deadlift variation may make sense. Examples: If you want to train your erectors more, selecting a conventional may make the most sense. If you want to train your glutes more, using a sumo deadlift in your program may make more sense. However, if enhancing peak power output is prioritized in your sport, opting for the hex bar deadlift may be more beneficial. It is important to remember that no one ever does one program forever. You are allowed to and encouraged to, oscillate among deadlift variations. Using this strategy will help avoid overuse injuries as well as focus on relative weaknesses that one variation may be lacking.

As a coach, the deadlift variation that I choose for me and my clients at any given time is the one that I feel can make the most progress within the scope of a program. For example, if one can add 40 pounds to the sumo deadlift in 6 weeks, but only 15 pounds to the conventional in the same amount of time, then one should probably do a sumo deadlift. With either choice, the same basic muscle groups will be trained, so everything will develop. There will also be a transfer of skill and strength development between all deadlifts. That is, if one spends 3 months developing a hex deadlift, without doing sumo or conventional deadlifts, both of those lifts would have improved because of the close nature of all three of these lifts. Getting better at one means getting better at the other two. So select the one that will make the most progress at any given time.

While there are certainly differences among deadlift variations, for the most part, I would not be overly concerned with which one should be done past a certain point. If you like one more than the other two, train that one. While scientific studies provide valuable insights into the biomechanical nuances and muscle activation patterns associated with different deadlift variations, the practical application of this knowledge may vary depending on individual goals, training status, and biomechanical considerations, as well as preference and ability to adapt.

Amidst the intricate details of muscle activation and biomechanics for different types of deadlifts, it's important not to lose sight of the broader purpose of deadlift training. At its core, the deadlift is a fundamental movement pattern essential for overall strength, athleticism, and functional movement in everyday life. Regardless of the variation chosen, all deadlifts engage a multitude of muscles and contribute to overall physical development.

As coaches and athletes, the key lies in pragmatically applying this knowledge to optimize training outcomes. While scientific research offers valuable guidelines, the ultimate determinant of exercise selection should be based on empirical evidence and individual response to training stimuli. By prioritizing progress and adaptability within a structured training program, athletes can effectively leverage the benefits of deadlift variations while minimizing the risk of overuse injuries and addressing specific weaknesses.

In essence, the quest for the ideal deadlift variation is a journey of continual refinement and adaptation, guided by both scientific understanding and practical experience. By striking a balance between evidence-based practice and individualized programming, athletes can unlock the full potential of deadlift training to enhance performance, resilience, and overall physical well-being.

Sources:

Escamilla, R., Francisco, A., Kayes, A., Speer, K., & Moorman, C. (2002). An electromyographic analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts.. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 34 4, 682-8.

Piper, T., & Waller, M. (2001). Variations of the Deadlift. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 23, 66.

Salehi, K., Babakhani, F., & Baluchi, R. (2020). Comparison of Electromyographic Activity of Selected Muscles on One Repetition Maximum in the Sumo and Conventional Deadlifts in National Power-Lifting Athletes: A Cross-Sectional Study.

Andersen, V., Fimland, M., Mo, D., Iversen, V., Vederhus, T., Hellebø, L., Nordaune, K., & Saeterbakken, A. (2018). Electromyographic Comparison of Barbell Deadlift, Hex Bar Deadlift, and Hip Thrust Exercises: A Cross-Over Study. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32, 587–593.

Camara, K., Coburn, J., Dunnick, D., Brown, L., Galpin, A., & Costa, P. (2016). An Examination of Muscle Activation and Power Characteristics While Performing the Deadlift Exercise With Straight and Hexagonal Barbells. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30, 1183–1188.

Flandez, J., Gené-Morales, J., Juesas, A., Saez-Berlanga, A., Miñana, I., & Colado, J. (2020). A systematic review on the muscular activation on the lower limbs with five different variations of the deadlift exercise.

Moreira, V., Lima, L., Mortatti, A., Souza, T., Lima, F., Oliveira, S., Cabido, C., Aidar, F., Costa, M., Pires, T., Acioli, T., Fermino, R., Assumpção, C., & Banja, T. (2023). Analysis of Muscle Strength and Electromyographic Activity during Different Deadlift Positions. Muscles.

DISCLAIMER

The information in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider or medical professional before beginning any new exercise, rehabilitation, or health program, especially if you have existing injuries or medical conditions. The assessments and training strategies discussed are general in nature and may not be appropriate for every individual. At Verro, we strive to provide personalized guidance based on each client’s unique needs and circumstances.